Introduction

In March 2019, a STEM competition held aboard HMS Sultan, centred around the Royal Navy’s integrated systems, that I took part when I was in college. In this post, I aim to provide a comprehensive account of my involvement in this fascinating project.

Purpose of the challenge

Designed for young people aged between 14 and 21, the annual competition offers a unique opportunity to grapple with real-world challenges. Each year presents a new theme that aligns with current technological advancements. Participants also have the exceptional experience of spending a day immersed in naval life and an overnight stay on board HMS Bristol.

The challenge

Our task involved an integrated system where two remote-controlled (RC) vehicles a land-based recovery vehicle and a ship-vessel had to collaborate to retrieve a stranded helicopter and return it to safety, all manoeuvred using a single controller.

Project Execution

Over a span of several months, our team designed and constructed the RC vehicles. We were given a list of potential equipment, complete with costs, allowing us to exercise budget control meticulously. After conducting extensive research on the necessary core materials, we moved to the design phase, employing AutoCAD and Solidworks 3D for initial sketches. While we devised multiple designs, each with its own strengths and weaknesses, we eventually settled on a final version.

Assembly and Testing

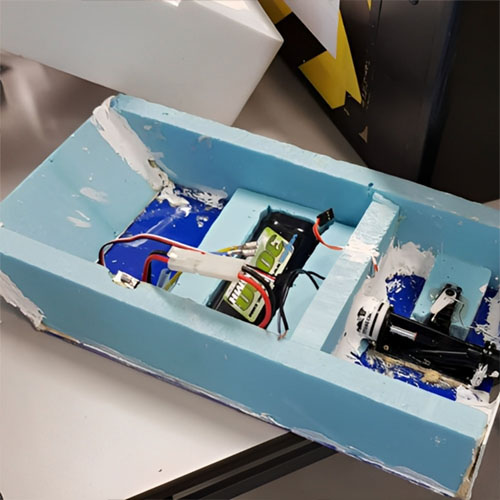

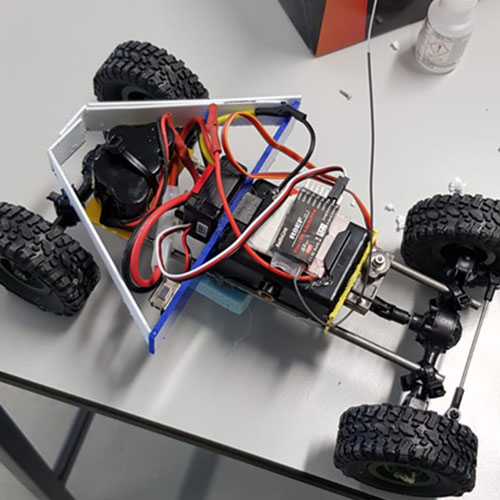

Upon receiving the materials, we commenced assembly. The vessel was crafted using blue styrofoam to ensure it was both waterproof and lightweight. An acrylic layer added extra buoyancy. Electronic components such as rudder, servo, battery etc, were carefully housed within the vessel’s base. Likewise, the car was designed to be compact and lightweight to facilitate its placement on the vessel alongside the “downed” helicopter.

Performance

We made two attempts to complete the challenge, one in the morning and another in the afternoon, which afforded us some time to refine our design. Despite our efforts, we were unsuccessful on both counts. Although the vessel operated well in water and the car successfully disembarked to collect the helicopter, we encountered design limitations. The crane hook could only move vertically, lacking the ability to manoeuvre in multiple directions. Additionally, the vessel’s propulsion system only allowed for forward motion, making control challenging.

Much like the vessel, the car was designed with compactness and lightness in mind, as both it and the “downed” helicopter needed to share space on the vessel without compromising its stability or operability.

There was a total of two attempts to complete the task. One was in the morning, and the other took place in the afternoon (which gave us time to improve and modify the design from the first attempt.

However, we were unsuccessful on both tries. The vessel was successfully moving in the water, and the car was able to leave the vessel and collect the down-bird helicopter. But you must be wondering what the issue was? Well… the crane hook could only move in a straight motion, either up or down. It could have been better if it had been able to move directions and not locked to a single axis. The other issue was the vessel’s trust was a water flush, so it only could move forward, it was difficult to manage (and we managed to control it), but the design could have been tweaked.

Learning Outcomes

The project was a significant learning curve, enriching my experience in multiple facets, from design and assembly to problem-solving and time management. Despite the setbacks, the entire endeavour was immensely enjoyable and instructive, sharpening my skills and deepening my understanding of what it takes to execute a complex project.